Going Open Source: Koha in an Academic Library

In December 2014, Stockholm University Library decided to implement the free and open source library system Koha as the circulation module in a larger system architecture for printed material. The goal is to have Koha up and running by late 2015. This guest post from Andreas Hedström Mace, a librarian and project manager working at Stockholm University Library, discusses some of the implications of this strategic decision and what it means for the library, as well as focusing on the benefits of open source library systems.

Stockholm University Library’s choice of Koha as the circulation module is related to an earlier strategic decision about how the library supports users’ information retrieval. The focus is now on providing and delivering content, regardless of where users find that content, rather than building search services of our own.

Choosing a new circulation system is difficult. To implement open-source software represents a risk and to replace a business-critical system is a difficult process. But there are advantages to be gained. Above all it’s about increasing control over such a central system, which in turn provides greater flexibility to adapt and develop important library services. As a result, Stockholm University Library aims to use the Swedish union catalog LIBRIS as our Online Public Access Catalogue (OPAC), and will not use any discovery service as a way to gather ‘all the material the library provides’. EBSCO Discovery Service (EDS) is currently used as a broad search for all articles and e-books, but will not contain the library catalog of printed materials. From the library’s point of view, EDS is considered as one article database among others. The library aims to provide all resources asked for by our users no matter where they discover those resources.

At an abstract level, the strategic direction taken by the library means that we are separating the circulation from cataloging and search services, both of which are provided by LIBRIS. Furthermore, we will separate flows relating to circulation and printed works from electronic resources and this, by extension, means separating circulation and Link Resolver/Electronic Resource Management (ERM). As a consequence, Stockholm University Library has no need for a Next Generation Library Management System, or even a traditional Integrated Library System (ILS) as such.

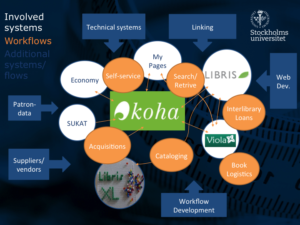

System Architecture

The system architecture for printed material will revolve around three pillars: Koha, LIBRIS and the internally developed book logistics system Viola (discussed in more depth here). These are all open systems and two of the three are open source. Viola is not yet open source but work is progressing towards that goal, as Viola is also being implemented at the Linnaeus University Library. In addition, there’s an ongoing development with LIBRIS at the National Library of Sweden. Called LIBRIS XL, it moves away from the MARC format and instead uses Linked Open Data in JSON-LD format.

Building a consistent and coherent system architecture, which integrates the various systems with one another, will be key in successfully adopting such a modular approach based on open source systems. There are also several data and workflows that can (and probably will) change in the process of integrating Koha with the other systems. This will demand much of staff and management with new prioritizations and further implications.

Open Source

One of the major strengths of Koha, as well as one of its limitations, is that it is an open source system. With open source software, the library’s dependence on a proprietary provider for a business-critical system is reduced, allowing greater control over data and software. It will bring development closer to the users – library as well as patrons – who have a greater ability to influence improvements of the system. Koha has a strong community with a number of users, libraries and businesses that contribute to its development, which is one of the system’s greatest strengths.

Community-based development can, however, also be a limitation. It requires increased cooperation and interaction with the community in order to get the development that the library wants included in future updates. Libraries that instead opt to develop themselves, regardless of the needs of the community, risk creating a proprietary version of Koha – ‘forking the system’ in technical terms. . This seems counterproductive, and highlights the importance of developing Koha within the community, even if this means that development takes slightly longer than it might otherwise. From Stockholm University Library’s viewpoint, the benefits of a more open development model far exceed the limitations.

Although economic benefits were not the main reason why the library decided to implement Koha, it is obvious that open source solutions are generally financially more viable than the use of proprietary systems. However, even though the system itself is free, there are development and hosting costs to consider. Also, according to the examined literature, open source library systems take up more of staff time in the form of development and adaptations. Moreover, during the migration period the library must bear the cost both of the previous proprietary system and the implementation of the new system. The library therefore needs to spend more initially, in order to save at a later stage.

Conclusions

Choosing a new circulation system is difficult. To implement open-source software represents a risk and to replace a business-critical system is a difficult process. But there are advantages to be gained. Above all it’s about increasing control over such a central system, which in turn provides greater flexibility to adapt and develop important library services.

It’s easy to get excited when an interesting new system is to be implemented, especially considering that the library has been locked in a sometimes unwieldy system for almost 20 years, but we shouldn’t delude ourselves. Koha is not a perfect system. It has an old code base written in what is becoming a languishing programming language, and is built primarily around the equally old MARC format. Koha is, however, a good alternative to its commercial competitors, with a strong foundation that allows several different workflows and should fit different types of libraries. Moreover, it has the potential to develop further. Advantages of implementing Koha at an academic library include:

- Increased control of a business-critical system

- Increased development and customization possibilities

- Vendor independence

- Lower costs

- Cooperation opportunities